9 Comparison between human and non-human skeletal remains

Introduction

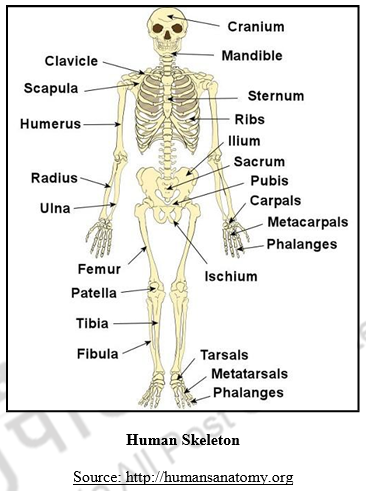

Humans are unique among primates in that they alone practice obligatory bipedalism and their skeletons show distinctive adaptations for this form of locomotion. Humans’ ability to regulate their body heat over long periods of heavy activity is also unique, as are their large brains that are highly developed organs that allow for technology, and diversity of culture and language. These qualities enable humans to travel over water, in the air, and into space. Humans live permanently in almost all terrestrial parts of the planet, and occupy inhospitable environments

Distinguishing between human and nonhuman bone is a task that should only be undertaken by a forensic anthropologist or individuals experienced in osteology. These include determining whether the suspected is actually bone, and if it bone, is it human or nonhuman? Numerous non osseous materials such as wood, pottery, plastics, or even stones can sometimes be mistaken for fragmented human bone. Before discussing whether or not a bone in human (indeed, at the start of any investigation involving suspected skeletal remains); the first thing the examining anthropologist must determine is whether or not the material is bone. Once the anthropologist is sure that the material is bone, they must determine whether it came from a human or a non• human animal. An experienced forensic anthropologist will have no problem distinguishing non osseous material from bone. Thus, basic knowledge of the human skeleton and nonhuman skeleton can help to save time when determining the forensic significance of whole or fragmentary skeletal remains. By examining the size, shape, and structure of a bone, an anthropologist can determine if it is human. In determining whether or not bone is human, it is important to distinguish between an area of the bone to bone articulation, an area of muscle attachment (origin and / or insertion) and area of relatively smooth bone that is neither an area of articulation nor an area of muscle attachment.

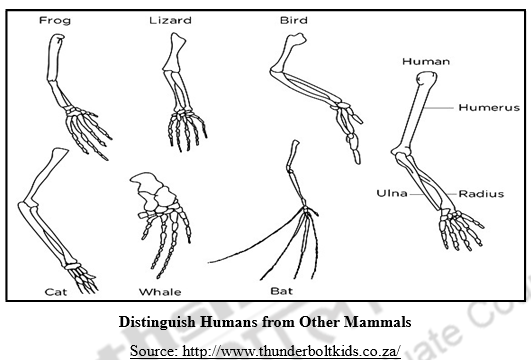

Distinguishing Humans from Other Mammals

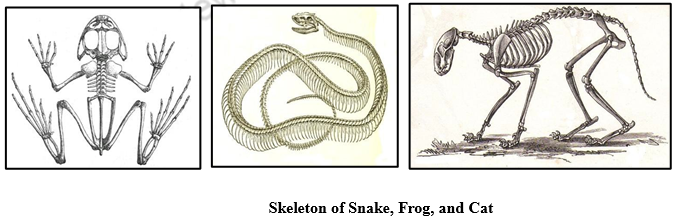

From an anatomical perspective, humans and other non – human mammals can be very similar in their skeletal components, and because humans are mammals, they possess many of the same skeletal characteristics. Upon gross examination, there are two main characteristics of bones that can help make the distinction between human and nonhuman bone easy and expeditious:

I. Maturity

Maturity aids in differentiating small nonhuman animals that, even after reaching adulthood, have bones that are similar in size when compared with juvenile humans. The most common human bones to be mistaken for animal bones are the bones of infants. They are sufficiently different from adult and even older children bones that they can cause considerable confusion.

Many animals have adapted to living environments that are very different to the environments we live in; therefore, they often possess distinct skeletal elements that humans do not have. The bones of birds are well suited to flying because they are very light. Additionally, birds have unique bones that are not found in the human skeleton, including the furculum (wishbone) and the synsacrum (an extended sacrum). The presence of these bones in a skeletal assemblage is a tip off that the bones are not human.

Some bony elements, though distinctive can be confused with human bones when fragmented. Pieces of sun-bleached turtle shell can mimic bits of the human skull. The key to distinguishing turtle shell from human remains is to examine the cross sections of the pieces. Human skull bones have an interior composed of spongy looking cancellous bone, but turtle shells do not.

II. Morphology

The second characteristic of bone that aids in the distinction between human and non human mammalian bone is morphology, or the shape of the bone. Because humans are bipedal they have distinct morphological features related to walking upright, which distinguish them from all quadrupeds that are adapted for four legged locomotion. Humans on the other hand, as bipeds, have a singular, central vertical axis of orientation that distributes all of the individual’s weight through a series of bony mechanisms designed to soften the impact of bipedal locomotion. As a result, human crania are centrally placed on the vertical axis, the spinal column has four slight opposing curves, the pelvis is broad and short, the femora are angled, the tibiae have thicker proximal surfaces for greater weight bearing, the feet have dual arch structures, and the upper limbs have less pronounced musculature and a greater range of motion.

There are generally three levels of identification that can be utilized to distinguish between human and animal bones.

- Gross skeletal anatomy,

- Bone macrostructure, and

- Bone microstructure (Histology)

1. Gross Skeletal Anatomy

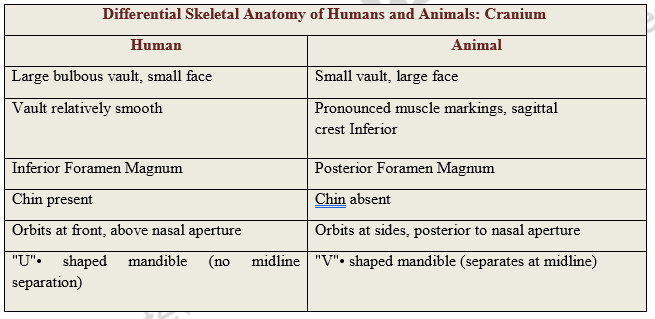

A. Cranium

- Cranial morphology differs dramatically between humans and animals due to the uniquely large brains that humans have compared to body mass. It is quite distinct because have large, rounded braincase and flat, or orthognathic, face in profile. Since animals (even large ones) have much smaller brains, their cranial bones are generally more curved and individually smaller.

- Animal mandibles are often “V” shaped in superior/inferior view and separate at the midline as opposed to the “U” shaped singular construction of the human mandible.

- Human crania are oriented on a vertical axis and the orbits are located in the front and above the nasal aperture. Animal crania are oriented on a horizontal axis and the orbits are located behind and lateral to the nasal aperture. These orientations also cause the position of the foramen magnum to be located inferiorly in humans and posterior in animals.

B. Dentition

- Dentition varies greatly between humans and animals, and even between different species of animals. Human teeth reflect a generalized design, including a mix of slicing (incisors), puncturing (canines), and grinding (molars) teeth. They are normally more rounded than animal teeth.

- Most animal teeth reflect specialized dietary adaptations. Grazing animals have more grinding teeth with specialized ridges and carnivores have more shearing teeth with sharp ridges. In addition, many animals have different dental formulas compared to humans.

- Adult humans generally have a compliment of 32 teeth, eight in each quadrant. This includes two incisors, one canine, two premolars, and three molars (2:1:2:3). Although highly variable, many placental mammals exhibit a generalized dental formula that includes three incisors, one canine, four premolars, and three molars (3:1:4:3).

C. Vertebral Column and Thorax (chest) Area

Human and non human have about the same number of vertebrae even in giraffes have only 7 cervical or neck vertebrae but the shape of the vertebral column and of the individual vertebral bodies differ.

- The vertebral column in a typical quadruped has single gradual curve from the neck to the pelvic girdle while the human has an “s” – shaped column. This difference in vertebral column shape is reflected in the morphology of the vertebrae as well.

- The quadruped typically has a longer, more cylindrical vertebral body than does the human, and the vertebral bodies are more similar in length from the neck region to the pelvis.

- The thorax (chest cavity including ribs) is deep and narrow in quadrupeds and shallow and broad in humans (which brings the centre of gravity of humans closer to the vertebral column.

- Ribs straighter in quadrupeds and more curved in humans.

Source: http://www.thunderboltkids.co.za

D. Clavicle

The clavicle maintains the distance between the sternum and the scapula and provides support for the shoulder girdle in humans whereas in some other mammals in which the forelimbs are used for manipulation, through it is vestigial or absent in many mammals and is therefore of limited use in species identification.

E. Scapula

When comparing human and other mammals, the dissimilarity in the shape of scapula can be very distinct and can quickly lead to a positive identification of human and non human remains. The scapula is elongated in most non human mammals, with the glenoid fossa (the point of articulation with the humerus), at the end of the long axis. In human the scapula is more triangular in shape, with the glenoid fossa along the most lateral surface.

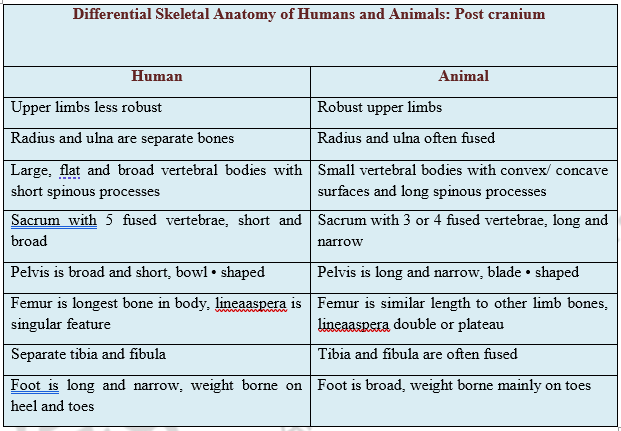

F. Radius and Ulna

Some larger mammal species have curved and fused radius and ulna. Recognition of these two bones immediately excludes humans as both the radius and ulna have straight diaphysis, and remain unfused throughout life.

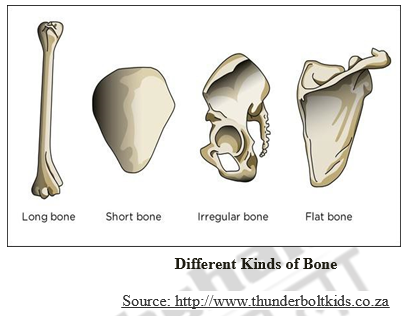

G. Femur / Long bone

Much of the difference in long bone anatomy between animals and humans is the result of pattern of locomotion. Depending on the level of development, juvenile human long bone may have unfused separate epiphyses. Conversely, those of small adult non human animal will display fused epiphyses. As a result, non human bones can be easily differentiated from juvenile humans by examining the level of bone maturity.

H. Pelvis

Distinguish Humans from Other Mammals

If a small pelvis is fused in to one unit, it will be a non human pelvis because a human juvenile pelvis of a comparable size is still in multiple pieces and the two adult pelvic bones of the human do not fuse at all unless there is pathological condition.

I. Tibia and Fibula

In number of small animals, including mammals, the fibula is reduced in size and is fused to the shaft of the tibia. In humans, the fibula does not normally fuse to the tibia unless there is pathology such as ossification of ligaments that serve to keep both bones articulated together. In addition, other morphological indicators that can be useful when differentiating small animals from human juvenile long bones may include non human skeletal features such as the fusion of fibula and tibia, and the curvature of the long bone shaft (diaphysis). The long bone shaft of small mammals may be noticeably curved where it is straight in healthy juveniles.

J. Foot

Mammals belonging to the order artiodactyls (hoofed mammals that have an even number of toes on each foot – two or four) can easily distinguished from humans by the presence of metapodials. In these animals (for example, deer, sheep, goat) the third and fourth metacarpals and metatarsals are fused together in to one structure early in development, and the generic name for both is metapodials.

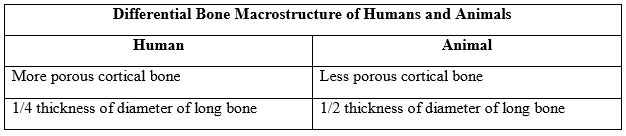

2. Bone Macrostructure

Animal bones have a greater density relative to size, less porous and thicker in cross section than the bones of humans. In humans, humeral and femoral cortical thickness is about ¼ of the total diameter compared to about ½ of the total diameter in animal proximal limb bones.

Some basic differences in animal and human bone macrostructure are:

3. Bone Microstructure (Histology)

In fact, if just a small bone fragment is recovered without any morphological indicators, the only way to identify whether it is human or nonhuman would be through histological (microscopic) examination or DNA analysis. In addition to the general gross morphology (shape) of the skeletal element, the external and internal textures of the bone are vital to diagnosing the bone and the species.

While the colour of the bone is not as important as other considerations when diagnosing species, it is important in determining tophonomic influences. Taphonomy is defined as anything that happens to a body after death. This includes the decomposition environment and patterns (climate, water, and insects, for example, and even the temperature of the laboratory in which the remains are stored, the post-mortem (after death) history of the remains is something one of the most important clue in solving a forensic case, and should never be dismissed when collecting evidence (including remains)

The microscopic structure of cortical bone is often diagnostic between humans and animals, although not practical in a field setting. Osteons in human cortical bone are scattered and evenly spaced whereas in many animals Osteons tend to align in rows (Osteons banding) or form rectanguloid structures (plexiform bone).

There are a several ways forensic anthropologists can tell the difference between animal and human bones. Firstly experts have a good look at them, and compare them to their knowledge of human/animal bone shape (morphology). Here they are looking for the right lumps and bumps on the bone in the right places, and the general proportions of the bone. Big animals such as cow, sheep, and horse have much thicker, denser bone than humans. If tap them, they sounds much more ceramic than human bone. Expert can also look at slivers of bone under the microscope. Big animal bone is built differently in the body, so has a different structure. Animals like sheep, cows, donkeys, giraffes etc have to get up as soon as they are born to avoid predators. This means their bone has to be laid down very fast and has to be very tough. Under the microscope, it has a sort of brick like structure, where the cells are laid overlapping on top of each other like bricks in a brick wall. This makes it very strong. Human bone, on the other hand, has longer to form and build strength, as when we are babies, don’t have to walk immediately. Humans bone cells are laid down more slowly around the blood vessels, and have a sort of concentric ring look to them, like the rings in a tree trunk.

Summary

Humans and animals have anatomical differences in skeletal composition, which distinguishes bones throughout all parts of their bodies. Human and animal bones are distinguished by gross skeletal anatomy, bone microstructure and bone macrostructure. Some human and animal bones are quite similar, making it difficult to identify isolated and fragmentary bones in the lab and the field.

- Cranial morphology, for instance, differs between humans and animals because of the large brain size that humans have compared to their bodies. Humans generally have smaller faces compared to their cranial vaults; the opposite is true for most animals, with the exception of some primates. Human crania are also oriented on a vertical axis; the layout is horizontal for most animals.

- Humans and animals also have different teeth layouts and mouth structures. This difference, called dentition, accounts for differences in human and animal dental formulas and tooth size and shape. For example, humans have small canine teeth and low molars, while animals have small or nonexistent canine teeth; these teeth are sharp and jagged in carnivores, and rounded or flat in herbivores.

- Postcranial human bones of the upper limbs are less robust than those of animals. Humans have separate radial and ulna bones, while those two bones are fused in most animals.

All mammals share a generalized skeletal template, meaning they all have the same bones in roughly the same locations: a skull, spine (which ends in a tail), ribs (which support the internal organs), and four sets of limb bones. If an investigator understand, and uses the basic principle, it will not be necessary to memorize the form of each bone of each species.

| you can view video on Comparison between human and non-human skeletal remains |